I’m a commis in a Chinese restaurant kitchen, this is what I do

I’m a 23-year-old Chinese Singaporean woman. After graduating culinary school in 2016, I started as a commis (also known as 马王, or minion) in a Chinese restaurant kitchen along Orchard road. This is a description of my everyday work, in English, written for friends and family who are curious.

The Structure of a Chinese restaurant kitchen

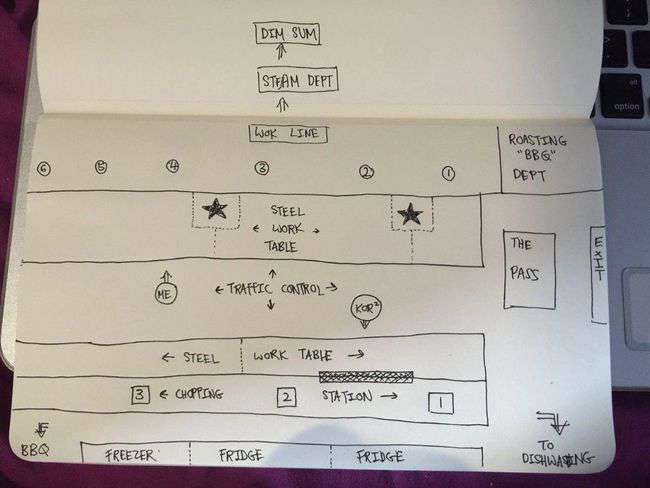

I drew a diagram of what our kitchen looks like, from where I stand (I only know how to hand draw and then upload a picture, pls forgive incompetence):

Dim Sum, 点心: They make the har gow, siew mai, XLB (little soup dumplings), carrot cake, cheong fun, and many other forms of dim sum and desserts. Because nearly everything there is made by hand, from scratch, they start work at 7am to finish their prep before service starts at 11am. Since we only serve dim sum in the afternoon, they get off work at 5pm, or whenever they finish their scheduled prep for the day. They are usually considered a separate kingdom from The Main Kitchen and the roasting department.

Roasting/BBQ, 烧腊:This is where the Peking duck, braised duck, roasted sucking pig, soy sauce chicken, char siew, roasted pork belly, braised pig’s intestines, etc. are made. They have two work areas — the back, and the front. The back is where all the heavy prep work is done. Every day they have to wash, marinate, dress, and hang carcasses; as well as roast them in their huge apollo oven (it looks like a tandoor). The front (a tiny work space beside the main kitchen) is where they carve and plate their finished products. They don’t just prepare their own items, like an a la carte order of a Peking duck; they also make products for the main kitchen. For example, they have to produce char siew for the rest of the kitchen — dim sum uses a lot of char siew for their pastries; the main kitchen uses char siew in a Yangzhou fried rice.

The Main Kitchen, 厨房

When industry people say “kitchen” they often refer to any of these sub-sections, and not dim sum or BBQ:

Steaming, 上什/蒸锅/蛋扣 : They are located in right beside dim sum, and are responsible for anything from the main kitchen that requires steaming — for example, Teochew steamed pomfret, Cantonese steamed marble goby, steamed bamboo clams with fried garlic and tung hoon. They make the daily double-boiled soups, and are also in charge of preparing the sharks’ fin and sea cucumber (very labor intensive, time consuming products to prepare). Unlike the rest of the main kitchen sub-sections, they coexist very peacefully with dim sum.

Wok, 炉头/炒锅 : Most people are more able to understand this sub section of the kitchen. It’s basically where all the things are stir-fried or deep fried. Within the wok line (our wok line can accomodate 6, but most of the time we work with 4) there is a hierarchy.

Wok 1 is head chef, 老大/大佬. He makes the big and final decisions for the main kitchen. He doesn’t do much prep work. If there are orders for abalone, sea cucumber, alaskan crab, the expensive stuff, they go to him. But he is really more important as a political figure, not as a cook. Like a gang leader, or any head chef, he is supposed to enforce discipline and consistency in his kitchen. He is also supposed to protect the interests of the main kitchen, especially against Front-of-House and higher management, especially in disputes with HR. For this reason, people expect him to exhibit a lot of machismo and dominance, or else they consider him ineffective and weak.

Wok 2 is the sous chef. He is not as politically significant as the Laoda, but he is acting chief in Laoda’s absence. He schedules our duty roster. He may also cook the Very Expensive Things. Some corporations/restaurants that do Cantonese cuisine have a policy of hiring only Hong Kong nationals to occupy head chef and sous chef positions. Ours is one such company.

Wok 3 is expected to cook anything short of the Very Expensive Things. Although he is lower in rank than Wok 2, he is not necessarily less experienced.

Wok 4 is also known as the deep-frying wok, or the “tail wok”. It is usually occupied by a more junior person. If a whole fish needs to be deep fried, it goes to him. He also handles a lot of fried rice, ee fu noodles, fried bee hoon, stir fried carrot cake. Since the larger and heavier woks are all kept at his end of the line, he cooks off most of our sauces (XO sauce, black pepper sauce, chilli crab sauce, sweet and sour sauce etc. ), deep fries peanuts, cashews, walnuts, whole chickens multiple times a week. He has an enormous role in prep. This person must work very quickly, and must multitask well. When service gets very busy, he should be able to deep fry two different items while stir frying ee fu noodles, without losing his shit.

Woks 5 and/or 6 are opened when we’re descending into chaos and desperately need another wok guy to help out. That’s when a qualified person, who otherwise performs another role, goes on the line for the night.

Butchery, 水台: The person working in butchery has one of the most strenuous jobs ever. Our butcher happens to be the largest dude in the kitchen. When deliveries come, they go straight to his room. He is the one who has to wash cartons and cartons of vegetables alone, break down entire carcasses of cod, hack entire legs of Jinhua ham, chop crates of ribs into smaller chunks, etc. He has to lug boxes and boxes of stuff to and from the walk in freezer. These are on top of the fish and seafood he has to kill and clean. He mostly works with the heaviest cleaver.

Knife work, 砧板: This station is a line of three cutting blocks (literal blocks, they are very thick and heavy, for stability). People doing knife work slice and chop almost everything the kitchen uses. They also have to marinate all the meat, sliced fish, diced chicken, etc. They have a never ending list of things to do. They are also the first line to read and process order tickets. For example, an order comes for “Seafood fried rice, medium, +salted fish, on hold, no MSG, not too oily, VIP, split into 6 portions”. The relevant information to the dude at the cutting block is “seafood fried rice medium + salted fish” has to pass the ticket over with the correct amount of diced seafood, julienned lettuce, and a small handful of chopped salted fish. Then his job is done and he has nothing else to do with this order ticket.

The Center Line/Traffic control/Communications, 打荷: This is where I work, between the knives and the fire. This is the section most difficult to explain to outsiders. This is where the youngest, most junior people work. This is the section that is the least technically demanding (i.e. you can train a monkey to do this job), but it is the most physically mobile, and the most cognitively demanding position during peak hours.

I’ll first explain what happens when we get a single order, using the above example - “Seafood fried rice, medium, +salted fish, on hold, no MSG, not too oily, VIP, split into 6 portions”. The dude at the chopping board has already pushed the lettuce, diced seafood, and salted fish from his side to our side of the table. We take a quick glance at the order sheet. First, we grab a medium-sized portion of rice. Then we transfer everything from our side of the table, to the table directly accessible to the wok guys. We tell him, “no MSG, not too oily”. We then fetch a serving tray, six small plates, a small rice bowl, and a metal dish. The wok guy makes the fried rice, dumps it in the metal dish, then we portion the fried rice using the small rice bowl (so that every portion is in a neat little mound). This fried rice example is a very simple example involving a bit of communication between our section and the wok line.

Here is another example, involving more inter-department teamwork: an appetizer plate named 特式三拼

Let’s say there’s an order for this item for five people. The knife work dude will toss over 5 butterflied prawns and 5 mantou rings (the dimsum department makes these weekly, in huge quantities). I will have to dust the prawns in potato starch, garnish and decorate five plates on a serving tray, sear five pieces of foie gras, and have wasabi sauce and foie gras-mushroom sauce on standby. At the same time I have to talk to Wok 4 - “特式5位”. Sometimes he forgets what he has to do, so I will say “炸锅巴5件,wasabi 虾球5粒,打鹅肝汁”. He will do all that while I sear the foie gras. When the foie gras is almost ready, I will call BBQ. They will bring 5 individual portions of braised duck and tofu, and I will plate up and send the dishes out.

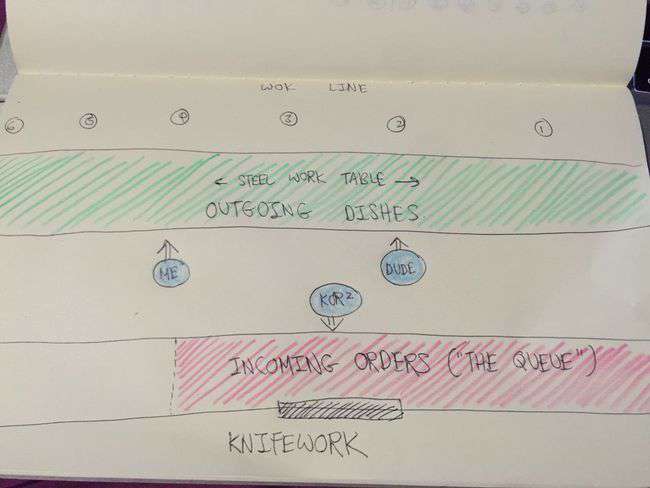

These are only individual examples. On their own they are very easy to execute. But on a busy night, between 630-9pm, the ticket printer doesn’t stop running. It will feel like the orders are coming in faster than we can send out dishes. This is when our roles within the section become specialized, and the concept of “queue” and “time” becomes especially relevant:

Incoming orders:

Highlighted in pink is the table where we process incoming orders. The shaded black box is the ticket machine, facing Knifework. Any order printed is first visible to them, although we have trained ourselves to read from the other side.

(As far as possible), according to the order in which they were printed, Knifework pushes ingredients with their order sheets over to our side, and they will all be received by the Korkor, who is the most senior person in the section. The first thing he will do is separate dishes “on hold” from “fire”. “On hold” means the order has been processed, but the customer doesn’t want it now. For dishes on hold, he groups them by table number. For dishes ready to fire, he sorts them according to

1/ Time of order. But it’s not rigid, it’s no big deal if an order printed at 7:35pm goes out before an order printed at 7:32pm.

2/ Whether it is a soup, appetizer plate, non-starch item, or starch item. Within the same time frame, items should be sorted to prioritize soups and starters first, and starch dishes last.

3/ Front of house mistakes - sometimes FOH barge in saying “I FORGOT TO KEY THIS ORDER IN PLS SAVE ME AND MAKE IT NOW”. We could say “no dis your problem”, or we could allow that item to jump the queue

4/ How angry the customer is. Some customers able to wait, others are not. If it’s been 15 minutes and a table hasn’t gotten their fried rice and are upset, we understand and will help that item move up the queue. But if the order has literally just been printed and a server comes in saying “HE’S PISSED OFF”, we do not entertain this request. Because we honor the concept of the queue.

Outgoing dishes:

When we’re busy I stand facing the table highlighted in green. On this table we cram at most 3-4 items in a wok guy’s immediate cue. Meaning he simply has to concern himself with clearing these few items as quickly as possible. The rest of the space is reserved for plating and garnishing. In a five minute time frame, I might have fish pan frying on the stove, tofu in the deep fryer, while plating lobster ee fu noodles for 10 people, while listening to wok sounds. We look down when we plate so we can’t see much else, but we are able to hear when a wok guy is done with a dish. If he’s done, we have to drop what we are doing and send out the dish. As soon as the immediate queue begins to clear, any one of us will fetch items from Korkor’s Organized Queue of Incoming Orders.

Stacking and efficiency :

Sometimes there’s a Yangzhou fried rice in Wok 4’s immediate queue, but he’s been busy and the fried rice hasn’t been started. Then Korkor receives another Yangzhou fried rice order, but if we go strictly by time, that Yangzhou fried rice would be quite further down the queue. Nevermind, we let it stack. The Korkor will call out “扬州炒饭有塔!” then he tosses it over to me. Stacking is inevitable because if we went item by item, according to time, we would literally die.

Prep work and miscellaneous duties:

There are many other small, routine, menial tasks that I do every day, that I don’t need to talk about here. Oil does not pour itself, I need to fill metal drums of oil for each wok guy about twice a day. Eggs don’t crack and separate themselves. Seasoning containers don’t refill themselves. And so on.

The more interesting prep work is in sauces. A great example would be XO sauce. We make roughly 10 liters of XO sauce every two weeks. When we realize we’re running low, we need to start dicing (very small dice) Jinhua ham and salted fish. This is very difficult. They are very tough ingredients. I do not like this part. Then we need to soak dried shrimp, steam and shred dried scallops, and grind chillies, shallots, garlic, and the soaked shrimp. We will weigh the required MSG and sugar. Then the XO sauce is ready to be cooked off.